By Millie Latack

As repinted from: Smithsonian Preservation Periodical Summer 2023 V2, Issue 2

The National Zoological Park (NZP) was opened in 1891 with the primary goal of conserving native species. It has evolved to be one of the top campuses for conservation studies and engaging educational experiences with more than 2,100 animals over 163-acres, as part of the National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute (NZCBI). With over a century of history within its gates, the NZP has pockets that tell the story of consideration and reflective design the Smithsonian Institution (SI) has for its animals and buildings. One such example is found in the Think Tank exhibit building at the southern end of the Rock Creek campus.

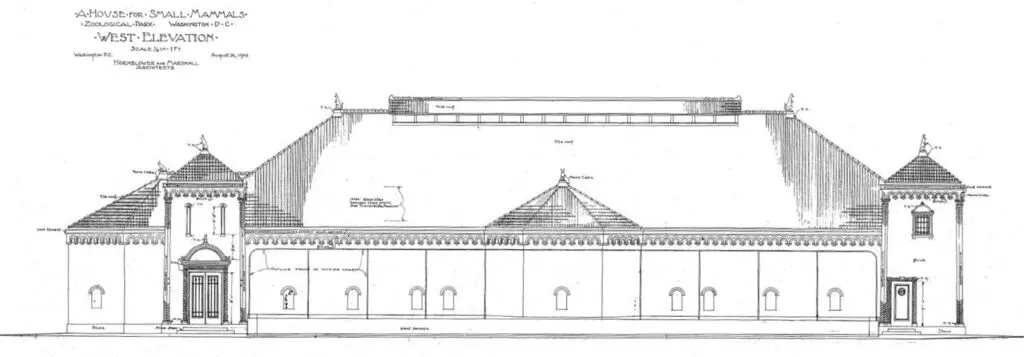

The Think Tank is the second permanent exhibit building constructed at the Zoo and is the oldest remaining structure in use today (fig. 1.). Drawings for the Think Tank, at the time called the “Small Mammal House,” were created by Hornblower & Marshall with design input by the then Zoo Superintendent Frank Baker, SI Secretary S.P. Langley, and Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. in 1903. This building was one of the last designed to complement the Zoo’s natural landscape; a concept originally established by Frederick Law Olmsted with the inception of the park. In a letter to Superintendent Baker, Olmsted, Jr. offers a critique of the early drawings produced by Hornblower & Marshall (fig. 2.) stating:

“it seems to me in general that it is not desirable to make the buildings of the Zoological Park striking or bizarre. Picturesqueness is perhaps to be desired, but it should be picturesqueness of the unobtrusive and modest kind.”

Four iterations of the design were considered before final approval was reached and approved by Secretary Langley on January 15, 1904.

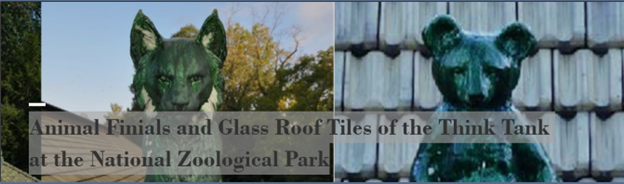

Construction of the Small Mammal House began in the same year and opened in 1905. The building was renamed the Monkey House in 1937 and renamed once more to the Think Tank in 1995 after the completion of the second major interior renovation and exterior addition on the northeast side; the first major renovation was in 1974-75. Throughout its evolution, the building never lost two important exterior design details that set it apart from the rest: spans of glass roof tiles and terra cotta animal finials. Both elements survived not only the renovations, but the extensive design discussions of the early 20th century.

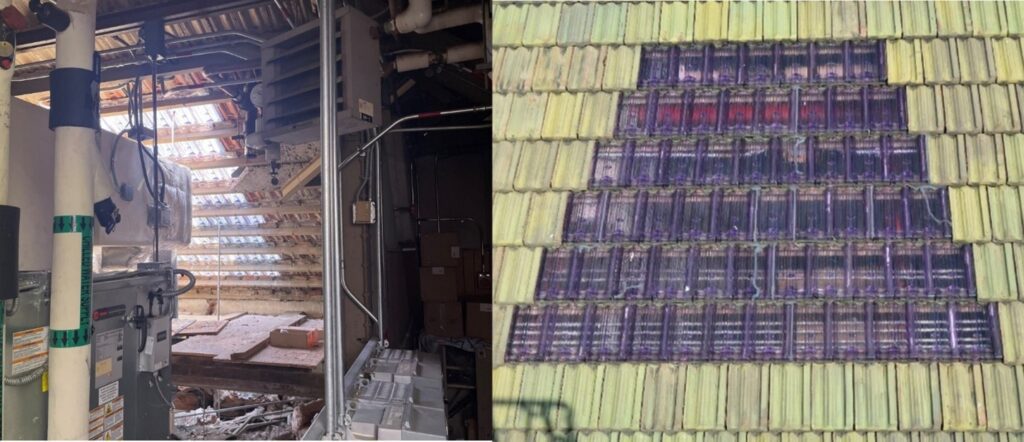

Olmsted, Jr. lauded the use of glass tiles to allow for natural light in animal spaces writing, “The essential feature…is the brilliant illumination of the cages by a continuous glass roof like of a greenhouse, and the illumination of the central corridor only by indirect light through the cages,” (fig. 3.). There are two large spans of glass tile on the north and south sides of the roof with smaller groupings of glass tile on the west tower and at the east end. During the 1974 renovations, a drop ceiling was installed covering the glass from the interior. The evolution of the exhibit needs in the ceiling make it difficult to expose the tiles for use of the natural light (fig. 4.).

These tiles were produced by Corning Glass with the same pattern as the terra cotta tiles, making a contiguous roof design. As for the purple, that was an unintentional finish. Manganese was often added to create a clearer glass offsetting impurities found in common glass production materials. Radiation from the sun oxidized the manganese creating manganese oxide which results in the purple hue (fig. 5.). There were specialty tiles installed with a flange that provided a pocket to support a shade frame. The frame allowed cover for animals that required protection from the sunlight. Some flanges can be seen on the south elevation where the only remaining exist (figs. 5 & 6).

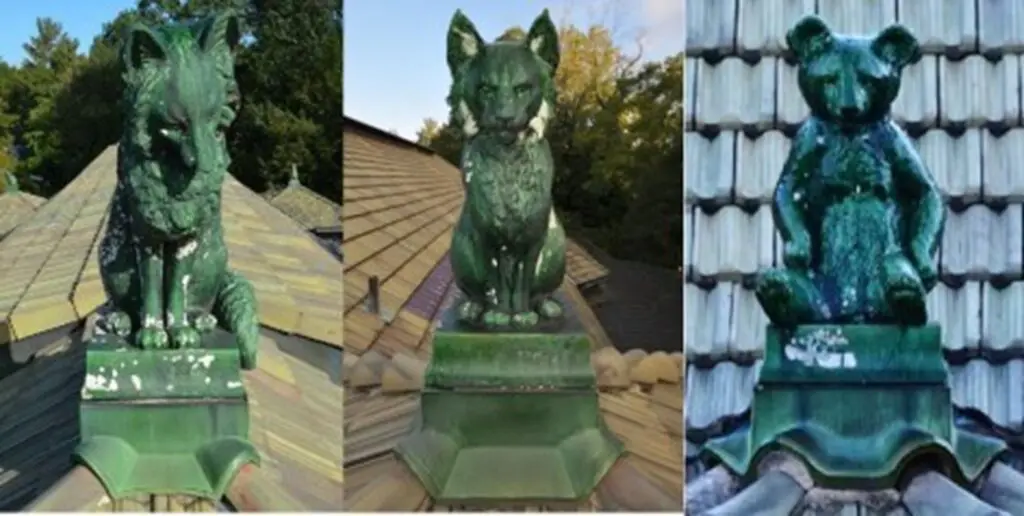

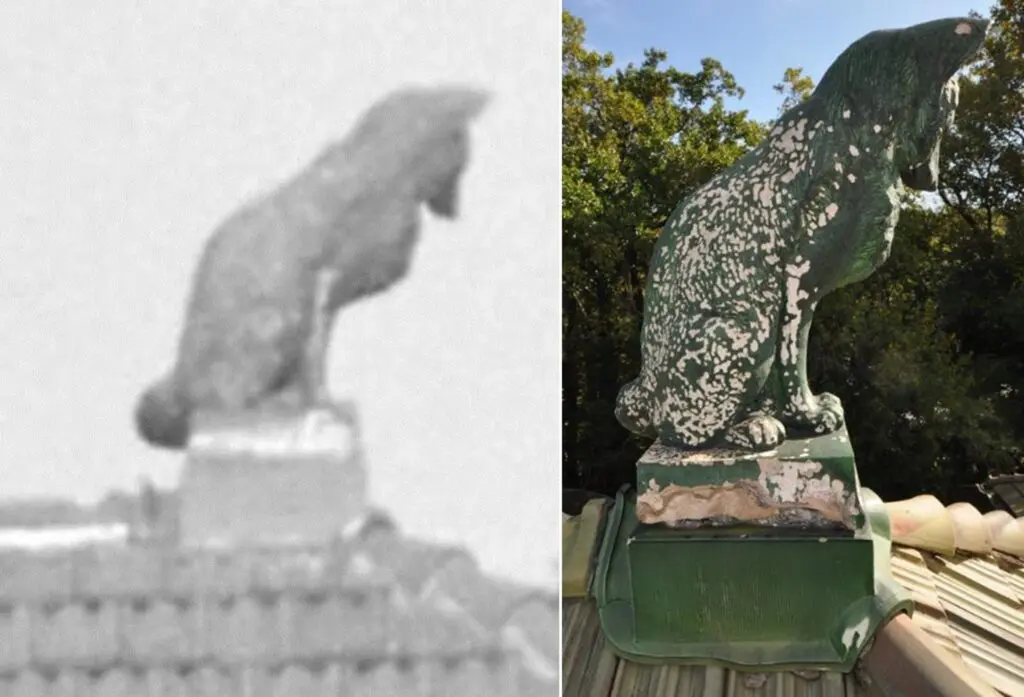

Accompanying the glass tiles are nine terracotta animal finials: two foxes on either side of the roof ridge, three bears on the center north, south, and west facades, and a Lynx at each of the four corners. These figures were the first public sculptures at the Zoo and were revered during design by Secretary Langley as being integral to the decoration of this exhibit space. The terra cotta animals were manufactured by Perth Amboy Terra Cotta Company modeled after smaller sculptures created by Laura Swing Kemeys. These pieces are composed of two units mortared together with the subbase, the functional part mounted to the roof, and the statue (fig. 7.).

Terra cotta is a porous material like common bricks but produced with a higher grade of clay and cured at a higher temperature. Glazing on terra cotta products can eventually show fine cracks in the finish, called crazing, or spall due to the natural expansion and contraction from moisture absorption and temperature changes. These finials were finished with a green glaze which, over time, has done just that (fig. 8.). In 2017, a conditions assessment of the finials and tiles were done by AEON Preservation Services LLC. Most were found to be in general good condition with varying amounts of glaze and terra cotta spalling, cracking, and chemical deterioration causing changes in the color and appearance of the glaze. One particularly interesting aspect of the findings was that the suspected glaze spalling was found to exist within the same time as original installation. Historic photographs show identical “bare” spots on the animals (figs. 9 & 10). Despite these imperfections, the animal finials and now purple glass tiles add a unique finish to one of the Zoo’s most significant historic resources.

See more at https://ahhp.si.edu/